Red Flags: 7 Warning Signs That a 'Great' Company Might Be a Terrible Investment

A framework to what to look out for.

Some companies look incredible on paper.

They have amazing growth stories.

Revolutionary products.

Charismatic leaders.

But beneath the surface... lies danger.

businesses can still wreck your portfolio if you miss what's hiding beneath the surface. While nobody picks winners 100% of the time, I've found that avoiding disasters matters more than finding the next Amazon.

Nobody bats a thousand in investing. But the folks who build serious wealth often do one thing exceptionally well: they sidestep the big losers.

Today, I’m giving you the lowdown on seven critical red flags. These are the tell-tale signs that a supposedly great company might actually be a rotten investment waiting to wreck your portfolio.

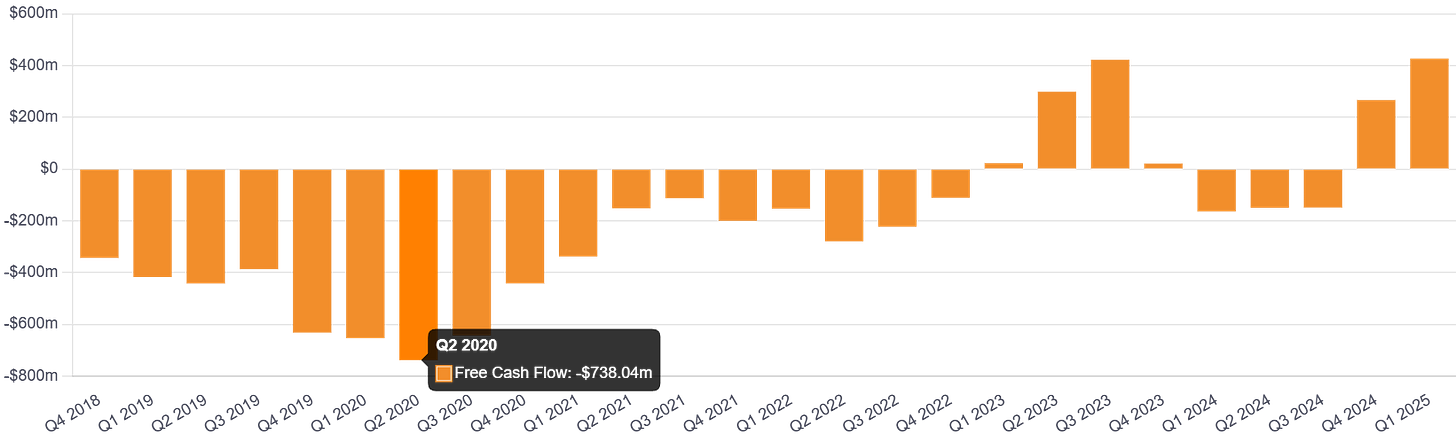

1. Cash Flow Doesn't Match the Story

If a company claims it's raking it in, but the cash flow tells you otherwise… trust the cash.

Accounting profits? They can be fudged in a million ways. But actual cash – the green stuff moving in and out – is a lot harder to fake. This gap between reported earnings and cold, hard cash is often the first hint that something’s fishy.

Real-World Example: Luckin Coffee

In 2019, Luckin Coffee was China's coffee darling, reporting explosive revenue growth and a rapidly expanding store count. But a crucial red flag was hiding in plain sight: the company was burning cash at an alarming rate.

While reporting $125.3 million in revenue in 2018, Luckin posted a stunning $241.3 million net loss. Even more concerning, the company was aggressively expanding without demonstrating its business model could generate positive cash flow at the unit level.

In April 2020, Luckin admitted to fabricating $310 million in sales. The stock collapsed from a peak of over $50 to under $2, destroying shareholder value.

Key Metrics to Watch:

Operating Cash Flow (OCF) to Net Income ratio: This should typically be close to or above 1.0. When a company consistently reports profits but generates significantly less cash, something may be wrong.

Free Cash Flow (FCF) trends: Watch for companies with consistently negative FCF despite reporting accounting profits.

Working capital changes: Sudden, unexplained increases in accounts receivable or inventory that outpace sales growth can signal aggressive revenue recognition or channel stuffing.

How to Spot This: Always look at the cash flow statement right next to the income statement. If you see profits going up but cash flow going down for several quarters, start digging. The management discussion section in reports will often reveal (or very carefully avoid explaining) why.

2. Debt That Could Sink the Ship

Debt itself isn't evil. Used smart, it can fuel growth and boost returns. But too much debt makes a company fragile. It can turn what should have been a temporary hiccup into a full-blown disaster.

Real-World Example: Valeant Pharmaceuticals

Valeant (now Bausch Health) built its business on a simple formula: acquire pharmaceutical companies using massive amounts of debt, slash R&D spending, and dramatically raise drug prices.

The debt numbers were wild. By 2014, Valeant owed $15.2 billion – almost double its yearly revenue. Its debt-to-adjusted-EBITDA ratio hit about 5x. Most industry watchers get nervous when that number goes above 2-3x..

When regulatory scrutiny hit its pricing practices and accounting scandals emerged around its relationship with Philidor (a specialty pharmacy), the company couldn't weather the storm. The stock collapsed from over $250 in 2015 to around $10 in 2016.

Key Metrics to Watch:

Debt-to-EBITDA ratio: Generally, anything above 3-4x for mature companies signals high leverage risk.

Interest coverage ratio: How many times can the company's operating earnings cover its interest payments? Below 2x is concerning.

Debt maturities: Watch for companies with large upcoming debt maturities that might need refinancing in tough market conditions.

How to Spot This: Check the balance sheet and debt footnotes in quarterly reports. Pay attention to off-balance-sheet obligations and lease commitments that function like debt but might not be classified as such. Also watch for patterns of debt-fueled acquisitions that mask organic growth problems.

3. Accounting That Raises Eyebrows

Financial statements tell stories. Sometimes those stories are fiction.

Aggressive accounting doesn't always mean outright fraud, but it often bends the truth to make things look better than they are. These tricks are meant to hide problems, but they leave clues if you know what to look for.

Real-World Example: Wirecard

Wirecard, once Germany's fintech darling, collapsed in 2020 after admitting that €1.9 billion in reported cash simply didn't exist.

The red flags were numerous:

Cash and equivalents represented a staggering 48.8% of total assets (€2.86 billion out of €5.85 billion) in 2018 – unusually high for a payment processor

The company relied on opaque third-party arrangements in Asia to process payments and supposedly hold cash

Complex corporate structures made it difficult to trace transaction flows

When pressed, management aggressively attacked critics rather than addressing concerns

Despite these warning signs, Wirecard maintained a €24 billion valuation before its fraud was exposed, eventually becoming worthless.

Key Metrics to Watch:

Non-GAAP metrics: Be wary when companies heavily emphasize adjusted figures that exclude "one-time" charges that somehow appear regularly.

Revenue recognition changes: Sudden changes in how revenue is recognized, especially to more aggressive methods, warrant scrutiny.

Unusual asset concentrations: When one asset category (like cash or goodwill) represents an abnormally high percentage of total assets compared to industry peers.

How to Spot This: Read the footnotes! This is where companies bury important details about accounting policies, deals with insiders, and how management explains (or doesn't explain) the results. Also, watch out for changes in auditors or fights with auditors – that can mean they're arguing about accounting methods.

4. Management You Can't Trust

Great companies need great leaders. More than that, they need honest ones.

A leadership team's integrity is probably the single biggest factor for long-term investment success. Without it, even the most amazing business idea can be ruined by executives feathering their own nests, making idiotic decisions, or committing outright fraud.

Real-World Example: WeWork

WeWork's 2019 IPO filing revealed shocking governance issues centered around founder Adam Neumann:

Neumann personally owned properties that he leased back to WeWork

He charged the company $5.9 million for the trademark "We" (which he later returned under pressure)

He maintained voting control through a multi-class share structure despite owning a minority economic stake

Family members held key positions without clear qualifications

His personal use of corporate assets, including private jets, raised serious concerns

These governance red flags, combined with WeWork's massive losses ($1.9 billion on $1.8 billion revenue in 2018), led to the IPO's collapse. The company's valuation plummeted from $47 billion to $8 billion, eventually leading to bankruptcy in 2023.

Warning Signs to Watch:

Related-party transactions: When executives or board members do business with the company, conflicts of interest arise.

Insider selling: Excessive or poorly-timed selling by executives can signal a lack of confidence.

Excessive compensation: Pay packages disconnected from performance or drastically higher than industry peers.

Dual-class share structures: These can entrench management and reduce accountability.

How to Spot This: Read the proxy statements. That's where companies have to disclose deals with insiders and how much they pay executives. Check insider trading records to see if execs are selling. And listen closely to how management answers questions from analysts – if they're cagey or get nasty when asked reasonable questions, that's a major red flag.

5. Capital Allocation Disasters

A company is ultimately worth what its management can do with its money. They need to invest in projects that make more money than they cost, and give extra cash back to shareholders when it makes sense.

Bad capital allocation – like overpaying for acquisitions, throwing money at low-return projects, or buying back stock when it's overpriced – can destroy a massive amount of shareholder wealth.

Real-World Example: General Electric

GE's fall from grace represents one of the most dramatic capital allocation failures in corporate history.

Under CEO Jeff Immelt, GE made a series of disastrous capital allocation decisions:

Overpaying for acquisitions in oil and gas just before the sector collapsed

Expanding GE Capital into risky areas that later required massive write-downs

Buying back stock at high valuations only to later sell shares at much lower prices

Maintaining an unsustainable dividend that eventually had to be slashed to a penny

The result? GE's market cap fell from over $500 billion in 2000 to around $95 billion by 2018, and the stock price dropped from over $30 in 2017 to around $10 by 2019, destroying hundreds of billions in shareholder value.

Key Metrics to Watch:

Return on Invested Capital (ROIC): Is it consistently above the company's cost of capital? Is it declining over time?

Acquisition track record: Do past acquisitions achieve projected synergies or require later write-downs?

Buyback history: Does management buy back stock at low valuations or waste capital on overpriced shares?

How to Spot This: Track the company's ROIC over time and compare it to its Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). Read management's rationale for major investments and compare actual results to their projections. Look for a pattern of value-creating decisions or value-destroying ones.

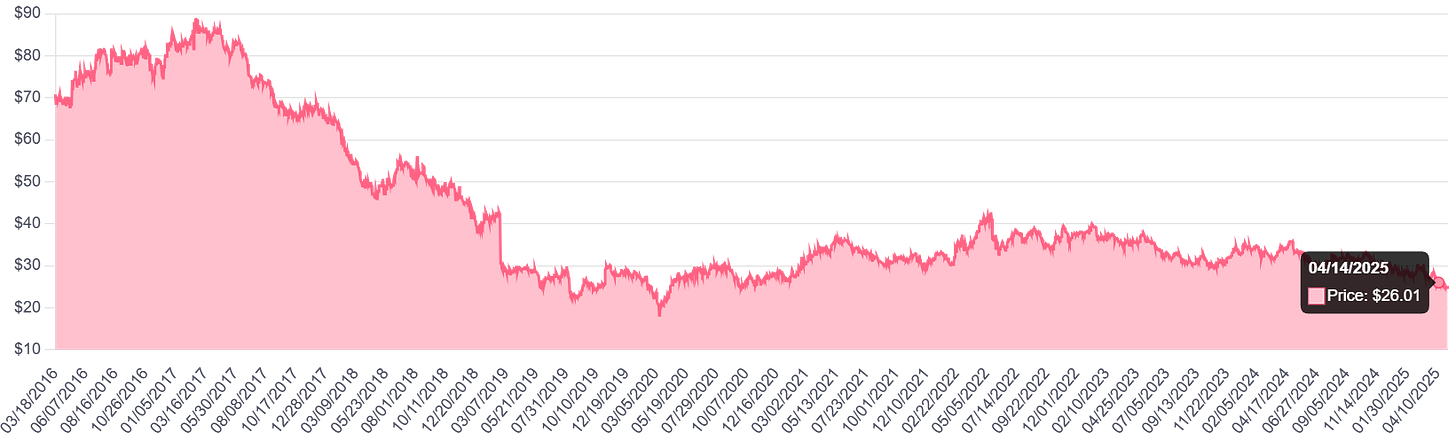

6. Valuation Disconnected from Reality

Sometimes, the market just goes gaga over a story. When that happens, company valuations can soar to levels that would require miracle-level future performance to ever justify.

No matter how awesome a business seems, price always matters. Pay too much for a company – even a good one – and you’re setting yourself up for lousy returns.

Real-World Example: Nikola

Nikola, an electric truck startup, went public via SPAC in 2020 and quickly reached a peak valuation of $34 billion – despite having zero revenue and no commercially available products.

The disconnect between valuation and business reality was staggering:

The company was valued similarly to Ford despite having no production vehicles

Its entire worth was based on promises of future technology and pre-orders without deposits

Management made bold claims about proprietary technology that were later revealed to be exaggerated

In September 2020, short-seller Hindenburg Research released a report alleging that Nikola had staged product demonstrations, including a video of a truck "driving" that was actually rolling downhill. The stock collapsed, and founder Trevor Milton was eventually convicted of securities fraud.

Warning Signs of Valuation Bubbles:

Price-to-sales ratios significantly higher than industry peers without corresponding profitability or growth advantages

Valuation metrics that require unrealistic future growth rates to justify

Market capitalizations that approach or exceed established industry leaders despite vastly smaller revenues or profits

Narrative-driven investing where price targets are based on stories rather than realistic financial projections

How to Spot This: Calculate implied growth rates from current valuations using reverse DCF models. Compare valuation multiples to industry peers and the company's own historical ranges. Question whether the future success priced into the stock is realistically achievable.

7. Deteriorating Competitive Position

A business is only as valuable as its competitive advantages. When those advantages erode – whether from technological disruption, changing consumer preferences, or competitive pressures – even formerly great companies can become terrible investments.

Real-World Example: Kraft Heinz

Kraft Heinz, formed through the 2015 merger of Kraft Foods and H.J. Heinz, represents a classic case of a deteriorating competitive position in the packaged food industry.

The warning signs were clear:

Stagnant or declining revenue (from $26.5 billion in 2016 to $26.2 billion in 2017)

Goodwill and intangible assets made up 84% of total assets ($101.4 billion of $120.2 billion), suggesting significant overvaluation of acquired brands

Changing consumer preferences toward fresher, healthier options threatened legacy brands

Cost-cutting could only drive margin improvements for so long before impacting product quality and marketing effectiveness

In February 2019, Kraft Heinz announced a $15.4 billion write-down of its Kraft and Oscar Mayer brands, cut its dividend by 36%, and revealed an SEC investigation into its accounting practices. The stock fell nearly 20% overnight and continued declining, destroying billions in shareholder value.

Metrics to Track:

Gross margin trends: Declining margins often signal pricing pressure or rising input costs that can't be passed on to customers – a sign of weakening competitive position.

Market share changes: Consistent loss of market share to competitors often precedes financial deterioration.

Revenue growth vs. industry: When a company consistently underperforms its industry's growth rate, its relative position is weakening.

How to Spot This: Compare operating metrics not just to the company's own history but to industry peers. Read industry publications and customer reviews to detect changing sentiment or emerging alternatives. Pay attention to rising competitive intensity in formerly protected markets.

Putting It All Together: Your Protection Plan

No single red flag guarantees an investment disaster. But when these warning signs appear in combination, they dramatically increase the risk of permanent capital loss.

Here's how to incorporate these insights into your investment process:

Create a pre-investment checklist that specifically looks for these seven red flags

Read beyond the headlines – dive into financial statements, proxy materials, and footnotes

Pay attention to short-seller reports – even if you disagree with their conclusions, their research often highlights legitimate concerns

Track key metrics over time, not just in a single quarter

Follow the money – how management allocates capital and whether insiders are buying or selling tells you what they really believe

Remember, avoiding disasters is just as important as finding winners when building long-term wealth. While no investor has a perfect record, learning to spot these warning signs can help you sidestep catastrophic losses that set back your financial goals.

The best protection against investment disasters isn't complex – it's a commitment to understanding what you own, recognizing red flags before they become obvious to everyone, and having the discipline to walk away when the warning signs mount, no matter how compelling the story.

Your wealth deserves that protection.

Thanks Michael, a nice overview.

Excellent points.

A primer on what to watch in an Annual Report and Income statement.